Every day, families across the nation rely on extended family members, friends, and neighbors (often referred to as FFN caregivers) to provide care for their children. These individuals play a vital role in nurturing the well-being of a vast majority of children in home-based, informal settings and are an essential part of today’s childcare system. While this form of caregiving is not new, it took on critical importance during the COVID-19 pandemic as licensed childcare facilities were forced to close their doors almost overnight. Suddenly, the support of family members, friends, and neighbors became an essential lifeline for parents who had nowhere else to turn for their childcare needs.

Many FFN caregivers were not prepared for this new reality. Often used to caring for infants and toddlers, FFN caregivers were now being asked to care for older school-age children who needed support navigating distance learning. The closure of public spaces like parks and libraries cut FFN caregivers off from the resources and public spaces they typically relied on to meet the needs of children in their care. And all of this was taking place during an unprecedented public health crisis which disproportionately impacted communities of color — the same communities more likely to rely on FFN care and of which the majority of FFN caregivers themselves are members.

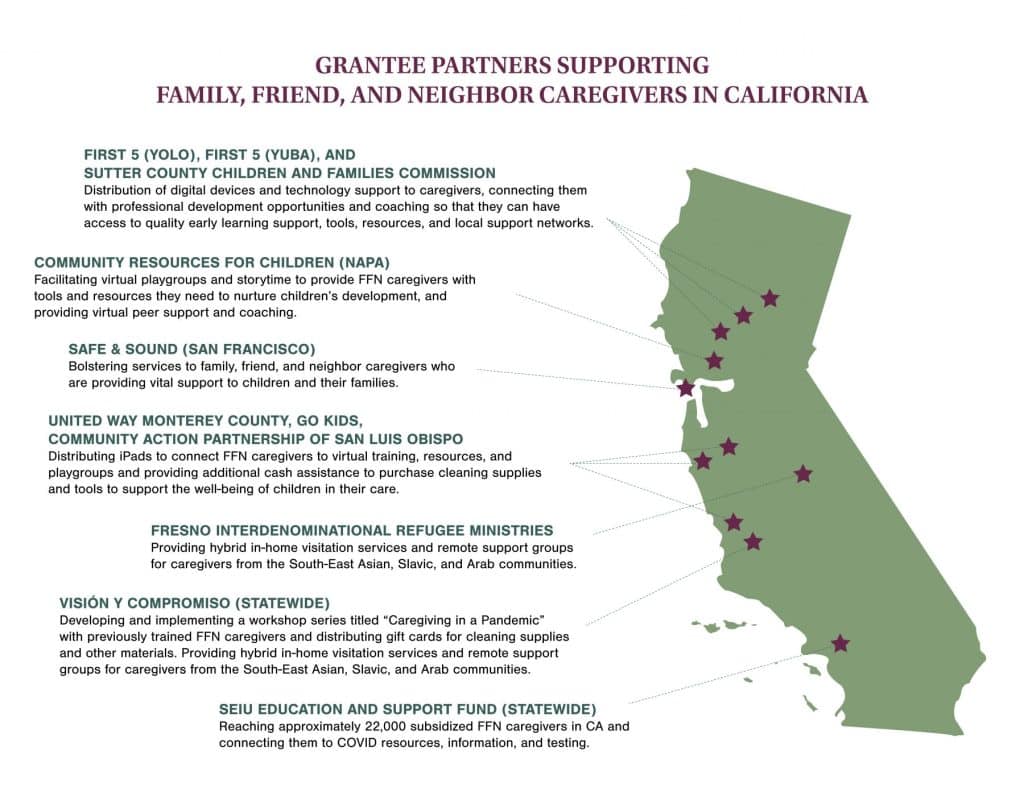

Because FFN caregiving has historically been overlooked by traditional public support systems, these caregivers do not have access to the same supports as traditional child care centers — things like professional development, educational materials for children, and connections to other caregivers. Often, local community organizations step in to address the need. As demand for FFN care increased during the pandemic and resources became scarce, the Packard Foundation recognized that the most effective way to support FFN caregivers and families would be by funding support to strengthen the work of these local community organizations.

Several of these grantee partner organizations gathered at a recent virtual convening hosted by the Foundation to share some of the valuable lessons they learned over the past year about what it takes to connect with and support FFN caregivers during a time of crisis.

Get creative to address the needs of FFNs

The economic recession and mass layoffs that resulted from the pandemic reverberated through the households of FFN providers and the families they serve. Many families struggled to access personal protective equipment, food, diapers, and other critical supplies. The rapidly changing context of public health guidelines during the COVID-19 pandemic further heightened constraints for FFN providers. They were left to make sense of limited and sometimes conflicting guidance on their own, navigating how to safely care for children in their homes while mitigating the potential risk to families.

“There was no book written about how to deal with services in a pandemic,” explains Beatrize Perez, associate director of children and family services of Safe & Sound. “Folks got really creative, and I think that creativity opened up a lot of doors and a lot of opportunities for the way that we do services.”

Many community organizations serving FFN caregivers innovated to adapt their services and programs to remain responsive to the evolving needs of FFN providers. They conducted play groups and provider support groups via video. They gathered information via a survey to understand what devices caregivers had access to and tailored virtual support accordingly. And they used a variety of channels — text messages, phone calls, WhatsApp, and Facebook — to communicate with FFN providers.

Invest in trust-building to connect FFN caregivers with resources and community

FFN caregivers are often socially isolated due to a variety of reasons: the nature of their work means they are at home all day caring for young children, they have not previously been included as part of the larger child care system, and many come from immigrant communities and communities of color that have historically been marginalized. This social isolation also makes FFN caregivers hesitant to interact with government agencies. At a time when community resources were limited, our grantee partners leaned in and served as the connective tissue between FFN providers, families, and resources. The trusting relationships FFN caregivers have with these community organizations alleviated their concerns and helped them access resources that they are eligible for but would otherwise not have known about. Organizations connected FFN caregivers to each other and to professional development opportunities they were seeking while also connecting children, families, and FFN providers to services that improve their physical, economic, and social well-being. Building these relationships between trusted intermediaries in communities and FFN providers is critical to engaging FFN providers over the long-term and promoting the quality of FFN care.

Many organizations stepped in to provide information on vaccines and support with signing up for vaccine slots, often partnering with local health departments to help answer questions. Mayola Rodriguez, program manager at GoKids, emphasized that “the key lesson here was just how much relationships and these connections matter. [The FFN caregivers] were able to share with us that they didn’t feel alone, they felt listened to and supported.”

Allocate time and resources to support digital literacy

The pandemic forced people to rely on virtual settings to connect. While this allowed community organizations to reach many more FFN providers, it also created several challenges in navigating technology for individuals who were not used to such settings. Several organizations distributed tablets and provided wireless hotspots to FFN providers to support their ability to join professional development workshops, access educational content for the children in their care, and remain connected during this time of isolation. Many had to step in and become IT specialists, helping FFN providers establish email accounts and download required applications to join virtual meetings, designing materials and resources in multiple languages and for the different devices that FFN providers relied upon.

Christine Barker, executive director of the Fresno Interdenominational Refugee Ministries, found this to be a difficult reality. “I think something that was a challenge is the amount of literacy that’s required to do a lot of technology — working with our families that aren’t necessarily literate in English or another language, problem solving and troubleshooting with them, how to get to where they needed to be on their phone or on their computer, how to access resources without being able to do it in person like we were used to.”

The pandemic forced many organizations to double down on their efforts to support the technological connectivity of FFN providers. It’s important that funders address this important form of support for FFN caregiving among our grantee partners.

Validate the important role FFN caregivers play by using intentional language

Many FFN care providers are motivated by family bonds and obligations and do not always recognize their role as caregivers. Validating FFN caregiving is more important now than ever, especially as FFN caregivers are also serving as teachers during distance learning.

Rita Baker, coordinator for First 5 in Yuba County, shared an example from her own family to underline the importance of using inclusive language to outreach: “My brother, who is an [FFN caregiver] has three grandkids from 4 and under [that he cares for]. He didn’t know he could qualify for [support] because he is just babysitting his grandkids.”

Grandparents, abuelas, tías, neighbors, and friends don’t always identify as caregivers. But by using language that reflects the critical role that FFN caregivers play, grantee partners make it easier for FFN caregivers to see the important work they do and understand they are eligible for support.

Our grantee partners serve as critical conduits of support to FFN caregivers — connecting FFN caregivers to each other, providing resources, delivering training, and affirming the vital role that FFN caregivers play in the lives of children and families. If we as funders and advocates care about FFN caregivers and supporting the quality of care they provide to young children, we must ensure that these organizations are well-resourced to continue carrying out their important work.