In the world of science, it isn’t always clear how a line of research will impact the world. It takes experimentation, tenacity, and the ability to follow curiosity wherever it leads. It’s that last element — that scientific freedom — that can be especially powerful. For some scientists, an unrestricted grant early in their career can be a catalyst for groundbreaking research and discovery.

That was the case for Dr. Moungi Bawendi, who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in October 2023. Bawendi credits his success in part to the unfettered support from the Packard Foundation in the early 90s.

“The Packard Fellowship was instrumental in getting my career started,” said Bawendi. “There is nothing like a large sum of unrestricted funds to spearhead innovation.”

“Unrestricted funding is critically important to innovation,” Bawendi said. “I think without unrestricted funding, we basically freeze out innovation.”

Dr. Moungi Bawendi

Bawendi had just arrived at MIT when he was awarded a Packard Fellowship in 1991.

The Fellowship is awarded to a group of about 20 innovative early-career scientists and engineers who are in bold pursuit of new spheres of research. Today, each Fellow receives $875,000 in funds that they can use over five years in any way they choose. This fellowship is one of the largest non-governmental fellowships for research in the U.S. and is a critical steppingstone for many Fellows in their career.

Bawendi says he still has the Packard Fellowship letter he received in 1991.

It’s signed by David Packard, who launched the Fellowship 35 years ago as a commitment to strengthening university-based science and engineering programs in the United States. Packard recognized that the success of Hewlett-Packard was borne, in large part, from research and development in university laboratories.

Throughout scientific history, countless discoveries have been made unintentionally, from penicillin to X-rays. Small breakthroughs that occur in a lab setting become catalysts for significant advancements in entirely different fields.

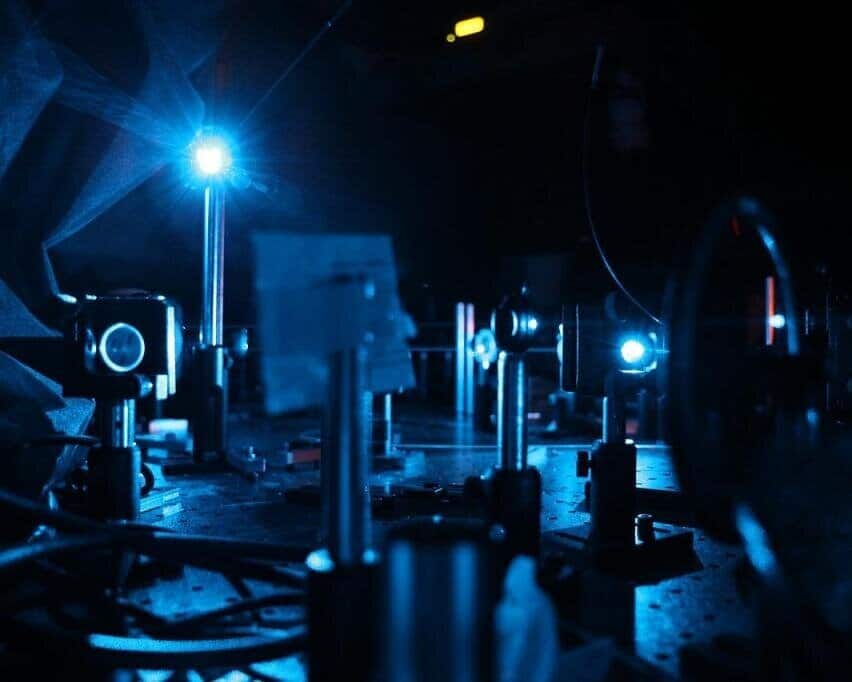

When Bawendi began his research in the early 90s, he had no idea his work would become instrumental in real-world applications. Bawendi was researching quantum dots: tiny semiconducting crystals whose properties, like color, can be adjusted as a function of their size. Quantum dots are extremely small, often in the order of nanometers (billionths of a meter).

Bawendi’s research built upon that of Columbia University chemistry professor Louis E. Brus, and Alexei I. Ekimov of Nanocrystals Technology Inc. who are credited with the discovery of this new class of materials. Brus and Ekimov were awarded the Nobel Prize alongside Bawendi.

One fascinating property of quantum dots is their ability to emit light and quantum dots can be engineered to emit specific colors. Bawendi’s breakthrough was developing methods to make high quality quantum dots that are stable and uniform. This allowed researchers and companies to achieve greater control over chemical production and produce precise and reproducible results.

Quantum dots are now used to tune the colors in LED lights and enhance the colors in television screens. They can also be found in other electronic, medical imaging and are expected to lead to advances in technology, solar cells and encrypted quantum information.

“The Packard Fellowship was instrumental in getting my career started."

Dr. Moungi Bawendi

Bawendi said the work for which the Nobel Prize was awarded was largely conducted between 1990 and the fall of 1992. He said his 1991 Packard Fellowship came just in time.

“I was saved because I didn’t have any money,” Bawendi said. “I had MIT startup funding which was quickly disappearing. Without that, I don’t know where I would have gone, what I would have done.”

Bawendi had hired two graduate students when he first arrived at MIT and used part of his fellowship grant to hire two more.

“The students are the heroes,” he said. “They do the work. We advise them, we guide them. They’re there every day in the lab. Being able to just buy things for them —equipment, chemicals, whatever— that allowed them to do the work.”

In reflection on his Packard Fellowship, Bawendi says he wouldn’t have done anything differently. He leaned on an indelible piece of advice he received from Brus, his post-doctoral advisor and Nobel Prize co-recipient,

“He said, ‘if you’re gonna burn, burn brightly,’ so I just took that money and I spent it,” Bawendi said.

And Bawendi’s investment has paid off. He was one of the most cited chemists of the decade from 2000 to 2010. He has received an array of awards and fellowships including a Nobel Signature Award from the American Chemical Society in 1997 and was selected as a Clarivate Citation Laureate in Chemistry in 2020.

Today, Bawendi continues to advocate for unrestricted funding as it provides scientists with the freedom to explore their research interests to take risks and push the boundaries of knowledge. He repeats that same advice Brus gave him to his students and younger colleagues.

“Unrestricted funding is critically important to innovation,” Bawendi said. “I think without unrestricted funding, we basically freeze out innovation.”

Since 1988, the Packard Foundation has awarded $477 million to support 675 scientists and engineers from 54 national universities.

Of the Packard Fellowship’s approach, Bawendi was unequivocal:

“There’s no other thing like this.”