“Dinosaurs capture the imagination like nothing else.”There are a few phrases that paleontologist Mary Schweitzer believes no scientist should ever use. “Everybody knows…” “I believe…” “Never…” Mary prefers data, facts, and rigorous methods. For her, these should drive a scientist’s conclusions. But what if the results raise more questions than answers? What happens when the data challenge everything an entire field of research has believed to be true for years? For Mary, the answer is simple: let the evidence lead the way. Her approach has led Mary to an extraordinary series of observations and experiments that have turned the field of paleontology on its head and challenged decades, if not centuries, of scientific dogma. And it has brought her, circuitously, back to her childhood. “I’m really lucky. It’s been a good ride,” she says, sitting on the back deck of her summer home in Bozeman, Montana, a cup of coffee in her hand, the sun peeking through the trees, her long, gray hair framing her face. “Certainly not what I would have predicted when I was in my twenties.”

A Return to Dinosaurs

To this day, Mary vividly remembers her first introduction to dinosaurs. “My brother was my hero growing up,” she says of her childhood in Helena, Montana. “He taught me to read and tie my shoes.” Although her brother left for college when Mary was five, he sent Mary books to keep her reading while he was away, including two about dinosaurs—“The Enormous Egg” and “Dinosaurs of the Flaming Cliffs.” Young Mary was hooked.

But Mary didn’t plan to study dinosaurs, at least not at first. She got married, had three children, and earned her undergraduate degree from Utah State University in Communicative Disorders; she planned to live her life as a mom and a teacher of deaf children. Mary was also a committed young Earth creationist—meaning she believed that the planet was only a few thousand years old and that the theory of evolution was false. Meanwhile, her interest in science didn’t wane, but “I wasn’t smart enough to study science,” she says. “That was the perception in my family and in my generation, so I didn’t take any science in high school or college beyond the minimum required.”

In her early 30s, Mary decided to go back to school in her home state, at Montana State University, to earn a teaching certificate. Out of curiosity, she audited a paleontology class taught by Jack Horner, whom she approached at the start of the class.

“I said, ‘I’m a young Earth creationist. I’m going to tell you you’re wrong about evolution,’” she recounts. “And he said, ‘I’m an atheist. Have a seat.’”

She accepted his invitation, and the ensuing semester changed her life. She couldn’t ignore the mounting body of evidence Jack presented that challenged her theories about the history of the world. By the end of the semester, she decided that the theory of evolution and evidence for an ancient planet were better supported than the idea that the earth was only a few thousand years old.

“I knew I wasn’t gonna throw away God,” she explains. “I can’t. I know him personally and I can’t pretend he doesn’t exist.” Instead, she came to see her passion for science and her religious beliefs as deeply interconnected—the more she studied the world through a scientific lens, the more it put her faith into perspective.

“It’s a false dichotomy that you can’t do faith and science,” she says. “If we could test and measure God the way we test and measure science, we wouldn’t need faith.”

At the same time, the class affected Mary deeply in another way. “It wasn’t a decision and it wasn’t intentional,” she says, but she found herself drawn back into her old passion for dinosaurs. She started volunteering at a museum helping prepare fossils, and then at Jack’s lab. Before she knew it, Mary found herself studying for her PhD in Biology.

Breaking the Mold

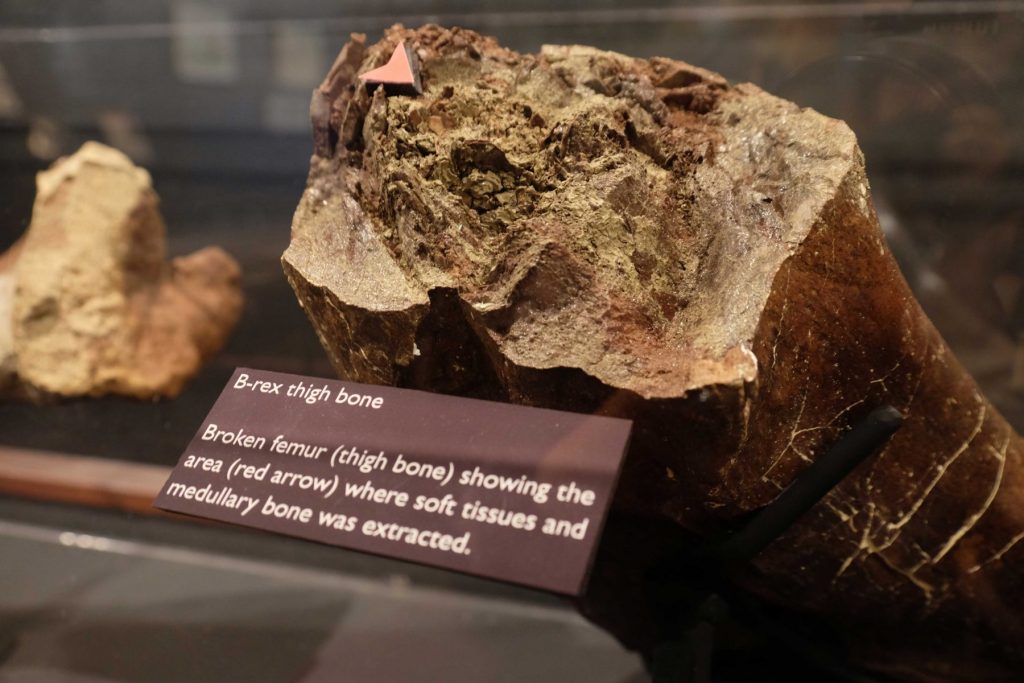

In 1990, while examining thin slices of bone from a Tyrannosaurus rex specimen, Mary and a colleague came across what appeared to be red blood cells. But Mary knew the field of paleontology considered it settled science that organic material like red blood cells can’t persist in fossils. When she brought them to Jack, she explained all the curious ways these items appeared to be red blood cells.

“And he said, ‘Well, prove to me they’re not.’ And that changed everything,” she says. “That changed the way I think and ask questions and do my science, because if you’re trying to prove something isn’t, and you’re trying to disprove your pet hypothesis, you remove an element of bias.”

Mary earned her PhD in 1995 and worked as a faculty adjunct in Montana until landing a teaching position at North Carolina State University in 2003. In 2006, Mary received the Packard Fellowship, which she used to pay for her talented lab technician, Wenxia Zheng. Wenxia’s expertise was crucial to Mary’s research. “I would have quit to become a greeter at Walmart if it weren’t for the Packard Fellowship,” Mary quips. “What I do is controversial and funding is very hard to come by, so having the freedom the Packard Fellowship afforded was pivotal in that progress that we made.”

Mary was fascinated with the idea of applying tools from other fields like histology, mass spectrometry, microbiology, and immunology to her own field of paleontology. She scoured the universe of scientific knowledge for cutting-edge techniques she could use to test whether she could disprove her hypotheses.

“If someone comes along with a really cool methodology, I’ll try it,” she says.

Along the way, Mary learned from a range of experts. She learned about immunochemistry from Seth Pincus and John Watt during her postdoc; she was grateful for the guidance of protein chemist Jean Starkey, who was on her PhD committee; and she explored genetics thanks to 2010 Packard Foundation Fellow Beth Shapiro, to name a few.

Against the Tide

As Mary pressed ahead with her research, her work led to a host of new discoveries about the range of preserved soft tissues present in dinosaur fossils. She found evidence of the first pregnant female dinosaur and discovered groundbreaking findings that supported the possibility of recovering proteins, including collagen, from dinosaurs. Although she published her work in prestigious journals along the way, Mary still faced an uphill battle in her field.

“I’m a middle-aged woman from Podunk, USA,” Mary says. “I don’t have a pedigree, and I’m coming back to school just trying to do the best job I can do with my science, and I unintentionally upended how a lot of people think about fossils.”

Mary received a lot of resistance, and still does to this day. She has challenged the conventional wisdom about fossils, and some of her peers even insist that her research must have been contaminated. However, according to Mary, dealing with criticism is one area where her continued faith has served her well as a scientist.

“I try really hard to have my work be a credit to God,” she explains. “So I’m not all that concerned about my own reputation, and I think that makes me a more rigorous scientist, because if I do the best job that I could possibly do, and if somebody comes along and proves me wrong legitimately, I don’t have to take that personally.”

Making a Difference

As passionate as Mary is about her work in paleontology, she is perhaps even more passionate about the power of her field as a teaching tool. She has seen dinosaurs inspire excitement in learners of all ages, from small schoolchildren who visit her lab filled with the wonder she felt at age five, to college students she brought with her in the summers to work in the field in Montana.

“Dinosaurs capture the imagination like nothing else,” she says.

Mary has mentored and guided many students into careers in science. In one case, Mary saw potential in a student in her class who was struggling, until she assigned him a project that sparked his interest. When he later applied to graduate school in chemistry, Mary went to a professor in the department to vouch for the student, and even offered to help pay for his education.

“He got one the most prestigious postdocs ever in a totally unrelated field, but he stayed with science because of dinosaurs,” she said. “It’s the coolest thing to watch somebody who doesn’t think they can be good at science want to get their PhD.”

In another instance, after watching 2002 Packard Fellow and biotechnologist Neil Kelleher’s presentation at the Packard Foundation Fellowship Annual Meeting, Mary pulled him aside to get coffee. She ended up discussing two of her postdocs, whom he later took under his wing.

A true advocate for the brilliant students she teaches, Mary says, “I’m very proud of all of my students. They are doing great things and making a difference.”

But Mary also believes that dinosaurs can do more than just inspire.

“Dinosaurs can still teach us something,” she insists. “Who has seen more periods of global warming and cooling than the dinosaurian lineage? If we can do molecular studies during these periods of climate change and see how dinosaurs responded at the molecular level, can we learn something about the direction our planet is going?”

Despite all of her discoveries and the many students she’s helped, Mary is always searching for ways she can contribute more. Perhaps this is why she will quickly tell you how proud she is of her three smart, successful children. Perhaps this is also why through her church, she has worked with formerly-incarcerated people returning to society and volunteered with an organization that rescues horses and pairs them with rescued girls. And perhaps on top of all of this, it’s also why Mary fosters kittens. But for this boundary-pushing, challenge-tackling scientist, this is simply the all-around good person she wants to be.

“I really do want to make a difference in the world,” she says. “The world is bigger than we are.”

Research Summary

My group’s goal is to recover endogenous biomolecules from ancient (usually Mesozoic) fossils demonstrating exceptional preservation. We seek not only to demonstrate that these molecules survive; we want to use them to address fundamental questions regarding evolution, physiology, and relationships as well as fundamental aspects of biomolecules giving them high preservation potential. We also seek to develop new methods to analyze fossils at the molecular level.