The deep-sea jelly Stellamedusa ventana lives in the mesopelagic realm of the ocean, at a depth between 500 and 1,800 feet — where sunlight doesn’t penetrate and divers can’t venture. Here, the translucent light blue jelly, whose name references its cosmic appearance, moves gracefully through the water like a shooting star in its impossibly dark surroundings. This magical organism — equipped with long, textured arms that trail behind it — was hidden in the deep sea until its discovery in 1990, when the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI) launched Ventana, a deep-diving submarine robot designed to go where no one had gone before.

MBARI came to life just three years before the S. ventana jelly discovery, following the Packard family’s successful establishment of the Monterey Bay Aquarium. The Aquarium’s creation combined David Packard’s growing interest in the ocean with the marine biology expertise of his daughters, Julie Packard and Nancy Burnett. MBARI blended these personal passions with a unique element — David’s vision of a groundbreaking institute based on peer relationships between scientists and engineers. This wasn’t just a whim. At Hewlett-Packard, David witnessed boundary-breaking discoveries when scientists and engineers pushed each other to advance together. Scientists asked engineers to develop new tools to solve existing problems. Engineers imagined inspiring technologies that expanded scientific frontiers. At MBARI this model was fundamental to structuring all of its research and development projects, an unprecedented approach in the field.

Previous explorers had already uncovered complex truths about the underwater world — observing the expansive ocean from shore, by boat, and by sending divers and vehicles into the depths. Yet, as MBARI President and CEO Chris Scholin reminds us, “the deep sea is the largest and least explored habitat on Earth.” Existing technology had limitations, leaving vast underwater realms a complete mystery. No one knew what lurked, undiscovered, throughout the depths, and at the bottom of the ocean.

MBARI’s team — scientists, engineers and marine operations specialists — came together to dream, dare, and think bigger than they could alone.

MBARI’s team — scientists, engineers and marine operations specialists — came together to dream, dare, and think bigger than they could alone. Driven by curiosity and immense talent, they set out to illuminate the unseen depths of the sea. The lack of technology wasn’t an obstacle — it was the perfect challenge for the young research institute. Scholin notes that these challenges “often took us in directions we could never have anticipated from the outset.” The team relied on the peer relationship of science and engineering to take risks, ask bold questions and create new technology in pursuit of deeper and deeper knowledge. Working in close partnership, engineers innovated the tools required to help scientists characterize and explore the ocean. Together they charted the course for a new age of deep-sea discovery.

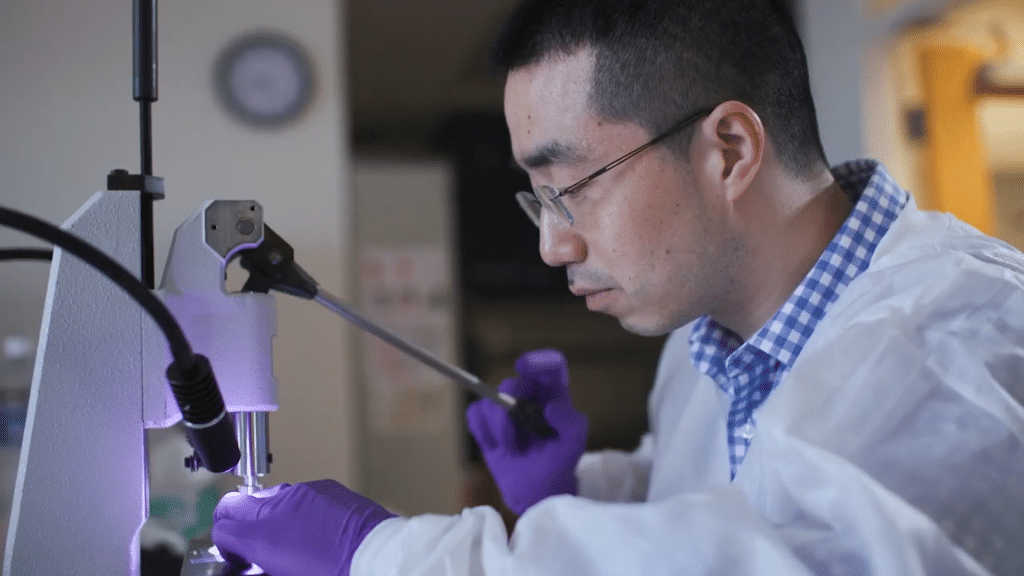

Out of this close collaboration emerged Remote Operated Vehicles (ROVs) like Ventana. Carted out to sea on an industrial offshore supply boat converted for ocean research, the Ventana’s bright red top sits above a cacophony of cables and instruments. A large crane must hoist the robot off the boat’s deck and submerge it in the water to begin its exploration. Equipped with this remarkable new tool, MBARI researchers journeyed out to sea each week — even when rough, rolling waves jostled the boat and crew. They readied their instruments and sent the new robot to be their eyes and hands on the ocean floor.

They were not disappointed. Just three years into their work, MBARI scientists reviewed footage of the S. ventana jelly, finding that unlike other jellies, which capture small food sources, this mysterious creature embraces and immobilizes large prey in its long, elegant arms. By bringing to light this rare species so far below the surface, MBARI exemplified the limitless potential of fusing ocean science in true partnership with engineering.

With each success, the team kept innovating. Autonomous Underwater Vehicles (AUVs), which could independently scan the ocean’s depths and sea floor, came next. With each discovery scientists posed new questions, driving engineers to develop new tools and equipping the vehicles with a myriad of available configurations to find answers. The ROVs and AUVs evolved to measure chemical and physical properties of water, collect samples and high definition video, map the seafloor in high-precision detail, and conduct experiments in the deep sea.

Through the development of this family of tools, MBARI developed a unique capacity to use underwater video technology and novel image processing software that formed the basis of the first deep-sea observatory in the United States. Since its founding, scientists have discovered and catalogued more than 100 new species, providing inspiration and data for other researchers for years to come, and offering the public a rare look at bizarre creatures and dramatic sea floor landscapes. At the same time, they also documented ongoing changes in basic ocean conditions and ecosystems that reflect a rapidly changing world.

Beyond exploration, the MBARI team also lent their tools to combat emergencies and threats to the underwater ecosystems they researched. During the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in April 2010, MBARI aided the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) by deploying an AUV to measure the spread of oil. As planes surveyed the surface for the extent of the visible spill, MBARI collected samples far below to document the depths the oil had traveled into the ocean ecosystem, providing critical insights to aid the cleanup effort.

Breakthrough discoveries require an acceptance that failure is possible and a commitment to the extended timelines necessary to achieve remarkable results.

From the beginning, The Foundation saw the potential impact of MBARI’s research and tools on global efforts to understand and protect the ocean. We also knew how difficult it is to secure funding for pioneering innovation, particularly in the ocean sciences. Breakthrough discoveries require an acceptance that failure is possible and a commitment to the extended timelines necessary to achieve remarkable results. The MBARI team needed funding flexibility and a committed, long-term partner. When new exploration opportunities surfaced, the team would need the agility to reallocate funds as appropriate to chase and capture elusive answers in the deep sea. With all this in mind, we implemented a forward-thinking funding model for MBARI, which included an annual private gift to the Institute to cover 75 percent of its annual operating budget. This freedom from yearly grant dependency has allowed MBARI to pursue unique, previously unsolvable, problems with inventive solutions.

In the early era of oceanography, scientists peered from the shoreline to see what they could learn about the ocean’s many mysteries. Later, they dove in to observe what life they could reach. However, if all we knew was what we could see or reach, we would know very little about the ocean’s secrets.

At the helm, MBARI President and CEO Chris Scholin sees this clearly. “The discoveries we make prove that there is still much to learn about the ocean, its inhabitants, and the role it plays in sustaining human civilization. Even in Monterey Bay — arguably the most studied patch of ocean in the entire world — we routinely discover things that are new to science; imagine what that means for the rest of the world’s oceans.”

Through the symbiotic evolution of science and technology, MBARI has ventured far beyond traditional research institutes, and far below the depths of the ocean previously explored. MBARI is constantly imagining, redefining, and expanding what we all know about the deep sea, and what we all must do to protect it and the life that it sustains.