At the David and Lucile Packard Foundation, our call is to create and support enduring solutions to the interconnected challenges that face humanity and nature.

Central to this mission is support for scientific inquiry, which often seeks to answer fundamental questions about the world and is essential for laying the groundwork for future breakthroughs and innovation. Through the Packard Fellowships for Science and Engineering, we invest in visionary minds exploring questions at the very edges of their fields and encourage them to push the boundaries of knowledge and discovery.

Each year, the Packard Fellowship Advisory Panel selects approximately 20 Fellows from 50 invited institutions to receive individual grants of $875,000, distributed over five years. These Fellows are early-career scientists and engineers working on cutting edge research across a variety of fields from evolutionary biology to astrophysics; neuroscience to nanotechnology.

Since its inception, the Packard Foundation has awarded nearly $500 million to support 715 scientists and engineers.

“The Fellowship program was unique – the mix of engineering and science, the generous support, and the flexibility it offered did not exist with other fellowship programs, and it allowed me to pursue riskier research,” said Frances Arnold, a chemical engineer, Nobel Laureate, 1989 Packard Fellow, and former Advisory Panel Chair.

The Fellowship grants are unrestricted funds that can be used in any way the Fellows choose. Fellows have used funds for everything from lab equipment to hiring students to childcare, all expenditures that ultimately make their work possible.

“The Packard Fellowship, in addition to allowing for funding for your research, allows funding for childcare, and part of what the grant did was to actually help us offset some of the really huge costs of childcare,” said Karine Gibbs, a microbiologist and 2012 Packard Fellow. “It also released the lab to start exploring different areas. I’m not sure we’d still be studying collective behaviors and bacteria if it wasn’t for the fact that Packard funded the first couple years of my lab to work on something that was a brand-new area.”

Addressing a Need for Early Support

The Packard Fellowship were inspired by David Packard’s passion for science and engineering and his commitment to strengthening university-based science and engineering programs in the United States.

He recognized that the success of the Hewlett-Packard Company, which he co-founded, was derived in large measure from research and development in university laboratories. Many of its inventions, like the first desktop calculator, the cesium-beam standard clock, and the HP Laserjet Printer series, were rooted in findings coming out of research institutions.

“My father very often said all of the progress made in the twentieth century was based on science of the nineteenth century,” said Susan Packard Orr, David Packard’s daughter and past board chair of the Foundation. “He really understood at a very deep level and believed that to make progress as a society and as a nation and as a world, we really needed to focus on advancing science and engineering both.”

Launched in 1988, the Packard Fellowships broke from the conventional research funding model by giving Fellows the freedom to take bold risks and pivot as their inquiries naturally evolved. The Fellowship was also designed to support early career scientists and engineers which often have insufficient funding relative to established research faculty. This approach was designed knowing that the benefits would also bring new opportunities to the students and post-docs working with the Fellows.

“The Packard Fellowship was my first major grant and it was such a boost in self-confidence. It allowed me to dream,” said Sangeeta N. Bhatia, a biological engineer and 1999 Packard Fellow. “I got to ask, ‘What am I really curious about?’”

The inaugural group of Fellows in 1988 came from an array of fields including mathematics, theoretical astrophysics, biology, and chemistry.

Unlocking Further Discovery

The Packard Fellowships quickly proved to be a huge boost to the scientists who received them, allowing them to pursue bold and imaginative ideas.

“The Fellowship gives you a great sense of belief,” said Enrico Ramirez-Ruiz. “When you have the Packard Foundation and the Advisory Panel believing in that’s incredibly empowering. And then the funding and the flexibility allow me to really explore areas that were thought to be not incredibly mainstream at the time.

Fellows have made groundbreaking discoveries, from CRISPR -Cas9 gene-editing technology that reshapes how we tackle diseases, to capturing a neutron star collision that confirms Einstein’s theories about the universe. They have also advanced our understanding of Ebola, aging, emerging virus strains, and developed innovations in microtechnology and disease detection.

Packard Fellows have gone on to receive the highest accolades, including Nobel Prizes in Chemistry and Physics, the Fields Medal, the Alan T. Waterman Award, the Breakthrough Prize, the Kavli Prize, and elections to the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine. Nobel Laureates include Wolfgang Ketterle, Frances Arnold, Jennifer Doudna, Andrea Ghez, Moungi Bawendi, and David Baker.

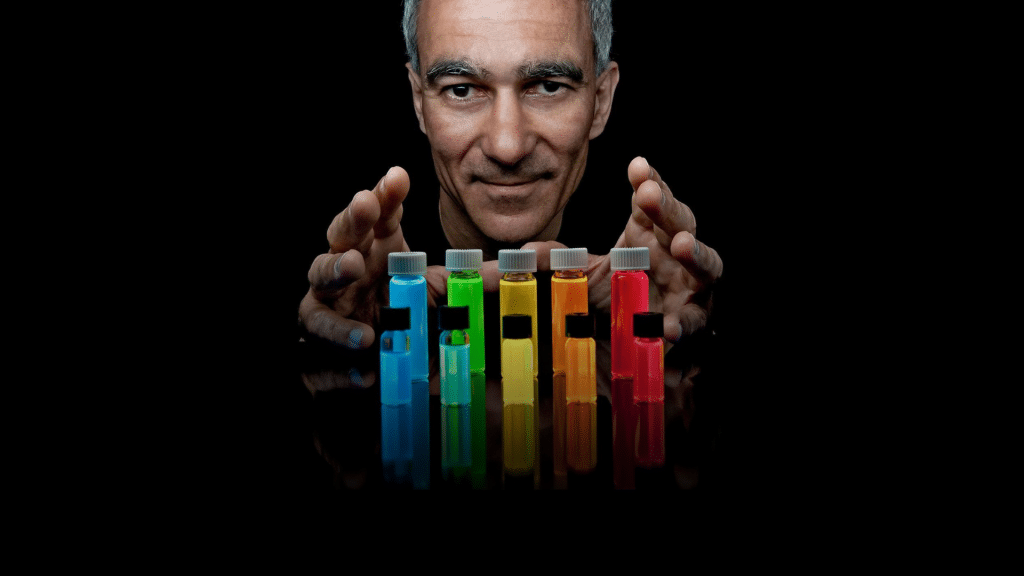

In 2023, Moungi Bawendi was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his work with the discovery and development of quantum dots. Bawendi continues to advocate for unrestricted funding like that provided to him by the Packard Fellowship early in his career as he believes it allows scientists to take risks and explore new fields.

“Unrestricted funding is critically important to innovation,” said Moungi Bawendi, Nobel Prize in Chemistry Awardee and 1991 Packard Fellow. “I believe that without unrestricted funding, we basically freeze out groundbreaking innovation.”

Building a Community

With more than 700 Fellows, the Packard Fellowships program has blossomed into a dynamic community of leading scientists and engineers. Each year, the Packard Foundation hosts an annual Fellows Meeting which provides a platform for exchanging ideas, challenging research, and sparking collaborations that span across disciplines. These gatherings have fostered deep mentorships and partnerships, with Fellows often working in the same labs and launching initiatives that extend far beyond their own fields. Some Fellows have even introduced innovative outreach efforts, like bringing telescopes to rural areas to inspire future generations of scientists.

“At the Packard meetings, they always remind you of why you were doing science in the first place,” said Teri Odom, a chemist and 2003 Packard Fellow. “It’s an opportunity to be curious again, for curiosity’s sake, because we have the opportunity to take a pause in the year to just be inspired by the new science from younger scholars.”

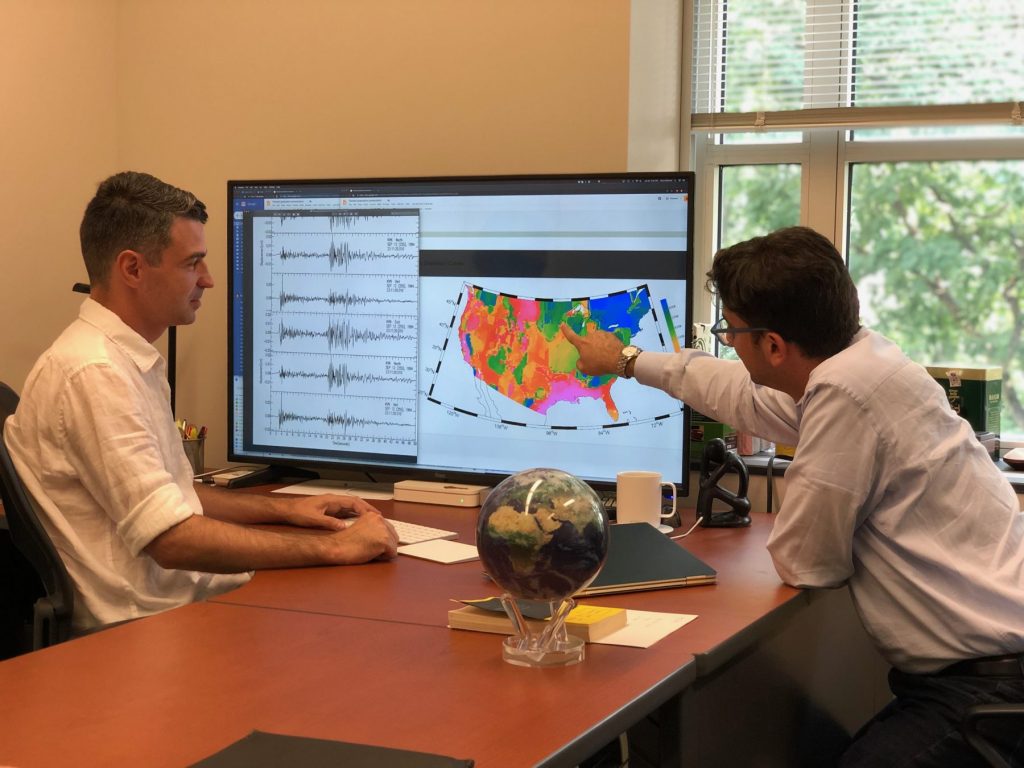

One such collaboration between Fellows arose when Brice Ménard and Vedran Lekic first met at the 2015 Packard Fellowship program’s annual meeting. Brice, an astrophysicist, and Ved, a geoscientist, seemed like an unlikely pair—one studying galaxies in deep space and the other examining earthquake waveforms in the Earth’s depths.

However, both scientists faced similar challenges in interpreting large, complex datasets that they could only observe from a distance. As they exchanged ideas during the meeting, they realized their methods for studying cosmic and geological phenomena had the potential to complement each other, sparking a unique collaboration.

Supported by the Packard Fellowship, which encourages interdisciplinary research without conventional boundaries, Brice and Ved used new algorithms to analyze seismology data in ways previously unexplored. Their partnership led to groundbreaking insights, mapping seismic variations across the U.S. with unprecedented detail.

“What’s been fantastic with the Packard Fellowship is this ability to just go and explore ideas without any boundaries,” said Brice Ménard of their collaboration.

Future Innovation

The Packard Fellowships continue to nurture a new generation of scientists and engineers, providing the freedom and resources necessary to pursue daring, original research. By removing traditional funding constraints, the Fellowship empowers its recipients to make groundbreaking discoveries that advance not only their fields but also the well-being of humanity and the planet. As the world faces increasingly complex challenges, the importance of supporting visionary thinkers remains more critical than ever.